I was interviewed by Revvell Revvati of The Book Crawler on Monday and we had a great time talking about happiness at work in general, and specifically about:

I was interviewed by Revvell Revvati of The Book Crawler on Monday and we had a great time talking about happiness at work in general, and specifically about:

-

Podcast interview with yours truly

-

Please join me on C4

I previously wrote about my good friends on C4 and how they’re helping Africa by letting people like you and me invest in small African businesses.

I previously wrote about my good friends on C4 and how they’re helping Africa by letting people like you and me invest in small African businesses.They are now moving into an open beta and are looking for more people to use the system. Won’t you join me there?

I’ve been using it for a while now and have already invested in a group of 6 women who want to sell auto spare parts and in Sulaiman Bulega (shown in the picture) who is going to expand the selection of office stationery in his store.

The really cool thing here is not only that helping people in the third world feel great – I also stand to get my investments back, with interest. So far, all the investments on the site have been repaid in full, meaning the default rate on the loans is lower than in banks in developed nations.

It’s really simple to join the site and to use it – but you will have to put at least 150 Euro (about 200 USD) in your account which you can then immediately invest in Africa.

In my opinion, THIS is how we will help the third world. Not by giving away money and aid but through investments and trade.

I urge you to join C4 – read all about it here and join here.

-

How to handle a laggard

What do you do about co-workers or employees who don’t pull their weight? Sheila Norman-Culp has taken a look at that situation and interviewed a few experts, including yours truly.

What do you do about co-workers or employees who don’t pull their weight? Sheila Norman-Culp has taken a look at that situation and interviewed a few experts, including yours truly.In the American workplace these days, teams are the hot commodity. And where there’s a team, there’s always one person whom others feel is not pulling their own weight.

So should the lazy worker be put on notice? Get more training? Be promoted? Be fired? Don’t laugh — experts say every one of those solutions could work.

I’m quoted as saying that the only cure for lazy employees is to fire a few of them, to put the fear of God into the rest. Or something like that – it’s been a while I since I talked to Sheila, I honestly can’t remember.

Related posts:

-

Can you be happy at work AND unhappy?

Gerardo Amaya asks this question:

Gerardo Amaya asks this question:I don’t know if you’ve already talked about this, but this thought really disturbed me. I heard a lady talking at a friend’s birthday party about her retirement. She said that she has never been happier since then, but the phrase that really makes me wonder was, when she said “I loved my work, but since my retirement I can finally do the things I really love”.

Looks to me like an oxymoron, but can this be true? She used to work as a financial adviser and she said that despite the fact that she is retired, she loves to make all the financial reports and calculations for her house budget because she misses it to much, so I guess she still loved the financial world.

Can you see the conflict here? So my question is, she loves her job, but she was wanting something else, but when she retires she had that something but misses her job. Is it possible that she loved her work but never realized it while looking forward for retirement? Can we say that she was happy and now she is not?

That’s a great question – how can you both enjoy what you do and yet long to put it aside in favor of other pursuits.

I don’t really have an answer for this. What do you think? Please write a comment, I’d really like to know your take.

-

I’m off to Estonia

I’m having a massively interesting week here. Monday I did a workshop for The Danish Union of Librarians. The workshop focused on making the libraries happier workplaces and on promoting better cooperation between management and union reps.

I’m having a massively interesting week here. Monday I did a workshop for The Danish Union of Librarians. The workshop focused on making the libraries happier workplaces and on promoting better cooperation between management and union reps.In my opinion, the one place where management and unions can always meet and work together is happiness at work. On all other areas, like salaries, policies, vacations, leadership, etc. they can easily end up on different sides. But everyone can agree that happiness at work is a worthy goal that serves both employees AND the workplace and that makes it a great place to start to improve working relations.

Today I’m going to Estonia to do a workshop for a new company called Arigato. Arigato is the newest, shiniest fitness center in the Baltic and a company with huge ambitions. Simply put, they want excellent customer service, and they’ve realized that the only way to achieve it is to have happy employees. That’s where I come in :o)

As you may know if you’ve watched Shogun as avidly as I have, domo arigato means thank you very much in Japanese, and one of the company’s core values is indeed gratitude. It’s very difficult to come up with new corporate values (everyone seems to end up with some variation of respect, openness, excellence, quality and trust) but gratitude is new to me. It’s a great idea though – as studies show that gratitude is a key to happiness.

After the workshop my wonderful girlfriend and I will be relaxing for a few days in Tallinn. I’ll be back on Monday, but I’ve set up a few posts to appear for the rest of the week, so things won’t have to go quiet here on the blog.

-

Just say no – to that evil company

My post on whether you can be happy working for a bad corporation got some great comments, including these:

My post on whether you can be happy working for a bad corporation got some great comments, including these:Michael Clarke writes:

One incident that’s stuck in my mind was an interview I had 24 years ago for a financial consultancy. The interviewer talked about money, about wealth, about owning yachts.

Then he began to talk about the losers, the [sorry, but I’m quoting] c**** who didn’t recognise money and its importance, that in five years you could walk away, that you could have other people doing the work for you. That the world had two kind of people – people like him and the “stupid c****” who didn’t understand. He went on and on. It was like talking to low-end devil.

Finally, he let me get a word in. “Sorry,” I said. “I’m afraid I’m one of the c****.” And I walked out. One of the more terrifying experiences of my life.

Like many in the Washington, DC area, I worked for a company whose largest clients were government contractors. Namely, a company that is the largest weapons manufacturer in the world. I hated the idea that my salary came from our contracts with them, even though I knew that we, as a company, were not at all related to the weapons industry.

Several years later, I was looking for a job, and got about a million calls from headhunters to work for this very same government contractor. I said no in the nicest way I could. They kept calling. Finally, I called them (in the middle of the night, so I didn’t have to talk to a person) that I was in no way interested in working for a company that is the world’s largest weapons manufacturer, was part of supporting the war in Iraq, and asked them not to call again.

And Scott M writes:

I was offered a very high paying job (4x salary increase) to work for an oil company in Alaska. When I told the person making the offer that I could not work for the oil industry (she was a headhunter) she acted like I was such an idiot…as if no one these days does that.

I still need to sleep tonight and anyone who appreciates the life this planet sustains needs to work for their conscience.

Happiness at work starts with not taking that job that looks good on the surface but which goes against what you stand for and I applaud anyone who has the guts to say NO in these situations.

-

Is flexibility at work good or bad?

According to an article in The New York Times, I.B.M. has been trying out a new vacation policy, in which fixed vacation rules are replaced by informal agreements between employees and their immediate supervisor. The guiding principle is that the work must get done. As long as this is the case, employees can take as much vacation as they want, even on short notice.

According to an article in The New York Times, I.B.M. has been trying out a new vacation policy, in which fixed vacation rules are replaced by informal agreements between employees and their immediate supervisor. The guiding principle is that the work must get done. As long as this is the case, employees can take as much vacation as they want, even on short notice.It’s every worker’s dream: take as much vacation time as you want, on short notice, and don’t worry about your boss calling you on it. Cut out early, make it a long weekend, string two weeks together — as you like. No need to call in sick on a Friday so you can disappear for a fishing trip. Just go; nobody’s keeping track.

The company does not keep track of who takes how much time or when, does not dole out choice vacation times by seniority and does not let people carry days off from year to year.

It’s not all peaches and cream and the article also mentions some downsides to this flexibility:

- Peer pressure to not take too much vacation

- Checking email and voice mail while on vacations

- Managers sometimes ask employees to cancel days off to meet deadlines

On the whole, I.B.M. employees like the arrangement and according to an internal survey, it is one of the top three reasons why employees choose to stay there.

This kind of arrangement is a sign of the times and we’ll be seeing much more of it. Just to mention a few examples, Californian software company Motek has done it for years, Best Buy are experimenting with ROWE, a Results Only Work Environment where only your results are measured – not the number of hours you work and the Brazilian company Semco let employees set their own working hours.

But is this much flexibility a good thing or a bad thing? Does it increase employees’ freedom or does it simply make it easier for bosses to manipulate and abuse their serfs?

That depends on who you ask. Richard Reeves in his book Happy Monday comes out completely in favor of it. Whereas Richard Sennett in The Corrosion of Character describes it as a terrible situation that is ruining our work lives.

Here’s my take: Happy companies naturally embrace this flexibility. In happy companies there is enough trust between managers and employees that it will the flexibility will be used to make people happy at work, and not to make them work more.

It’s true that it does put more responsibility on employees’ shoulders to actually take some vacation time, but seriously – we’re adults here, right? We should be able to tell when we need one/want one and do something about it.

Like I always say, if you want to be happy at work you must:

- Know yourself. If you don’t know yourself well enough to tell when it’s time for a vacation, then who will?

- Speak up. If there’s something you need, say so. Don’t passively wait for your boss to figure it out.

- Do something. Act on it!

In bad, abusive workplaces however, things are not that simple. Here it is normal to create all kinds of explicit and implicit pressures on people to work more and more, and in this case, flexibility simply becomes a license to abuse employees. Here, setting vacations according to contractual obligations or union rules offers way less flexibility, but it at least ensures that you get some vacation time at all.

It’s also true that different people like different levels of flexibility. Some people like to leave vacation planning completely open, others prefer to have it fixed years in advance. A truly flexible system accommodates both kinds of employees.

I do believe that flexibility is a good thing in and of itself and it’s a hallmark of all the happy companies I know that they offer very high levels of flexibility. I think flexibility comes from mutual trust and trust comes from being happy – as psychological studies confirm.

So if you want to have high levels of flexibility in a company, make sure you have high levels of happiness and trust first.

Your take

How much flexibility does your workplace give you? Is that a good or a bad thing? What makes it good or bad? Please write a comment, I’d really like to know.

Related

-

A question for the Spanish speakers out there

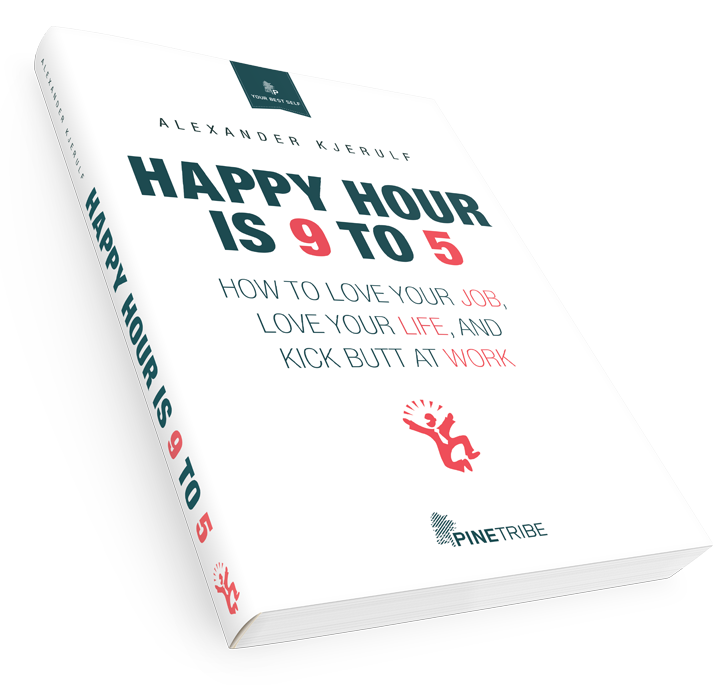

My book has just been translated into Spanish by Maria deVera of ContentSpanish who did a magnificent job. It will be available in Spanish on paper and in pdf very soon.

My book has just been translated into Spanish by Maria deVera of ContentSpanish who did a magnificent job. It will be available in Spanish on paper and in pdf very soon.I just have one question for ya: The title.

This is the title we’re going with: Nuestra hora feliz es de 9 a 5 – Cómo estar encantado con tu trabajo y con tu vida y ser un profesional excepcional.

It’s a pretty literal translation of the original English title Happy Hour is 9 to 5 – Learn how to Love your Job, Love Your Life and Kick Butt at Work.

How do you like the title in Spanish? Do you have a better idea? Do you think there’s a market for the book in Spanish?

Please write a comment, I’d really like to know your take!

-

Does social software make you happy?

I was challenged by Susanne Goldstein of The Social Age to write something about happiness at work and social software.

I was challenged by Susanne Goldstein of The Social Age to write something about happiness at work and social software. The question is: do all these fancy, new ways of interacting on the web like blogs, youtube, forums etc. make us happier at work and in life?

Instead of writing something, I made a short video-riff exploring the question with Thomas Madsen-Mygdal who is very much an expert on social software.

You can see the resulting video on Susanne’s excellent blog here: Does Social Software make us happy?

-

Can you be happy in an evil business?

My Dutch Pal Erno Mijland asks a very interesting question:

Last week I watched the film Our Daily Bread which is a documentary on how food is produced in Europe. It shows an industry in which there’s not a lot of respect for plants and animals: lots of poison, young chickens being thrown around, pigs transported in small boxes etc. etc.

Because I was a bit prepared these images didn’t shock me very much. What did shock me, were the scenes in which the workers in this industry where shown. People showing no emotion whatsoever in what they where doing, big automated halls where a worker works (and lunches) alone, people doing mind torturing repetitive work all day long.

It made me wonder: who could possibly be happy at work in these kind of conditions?

What a great question. The easy answer would be “No one. No one can be happy under these conditions.” But the truth is a little more complicated.

If you haven’t seen Our Daily Bread and you’re not squeamish, you can see a short clip from the movie here:

Interestingly, I’m currently reading a book called Gig, which simply consists of interviews with working Americans. I just read about the HR manager in a slaughterhouse, who talks about the same issue:

Last month, I hired eighty-five people and ninety-two left. That’s not uncommon. We’re bleeding people. I hire them and they leave… Some people will quit fifteen minutes after they get on the floor because it is so ugly to them.

The interview also has some graphic descriptions of employees walking around in a couple of inches of cow blood… No wonder so many people quit!

But this is not just about killing cows. Could you be happy working for a company that makes land mines? Or a company that pollutes the environment? Or a tobacco company? Or working for Microsoft? Just kidding!

The larger question is this: Can you be happy at work if you deeply believe that your workplace ultimately makes the world a worse place?

Here are some factors to take into account:

1: Mismatch between personal and company values is a huge stress factor

When your job goes against your personal values, you’re in a very difficult situation. This means, that on a daily basis you are doing things that you can’t defend to yourself.This causes what we might call values stress – a feeling of stress that comes from a conflict of values. This can be every bit as serious and damaging as the old garden-variety stress that comes from being busy.

Even if you’re not actually making the land mines – let’s say you’re just the receptionist – this may weigh heavily on you. Every single day.

2: You can temporarily ignore this mismatch

However, you can keep yourself from dealing with this stress factor simply by ignoring it. The human mind has a fantastic ability to shut things out and adapt. If you so choose, you can simply keep yourself from realizing that this is bad.You can focus on the good aspects on your job, have fun with nice co-workers, and even still take pleasure from doing your job well.

A lot of people certainly do this for a while, particularly when they really need the salary. But while it can enable you to be happy at work for a time, it is not a good long term strategy.

Even CEOs are not immune to this temporary blindness. Here, Ray Anderson, the CEO of Interface the world’s largest manufacturer of carpets, explains how he suddenly realized that his company was bad for the environment:

…it dawned on me that they way I’d been running Interface is the way of the plunderer. Plundering something that is not mine, something that belongs to every creature on earth.

And I said to myself “My goodness, a day must come where this is illegal, where plundering is not allowed. I mean, it must come.”

So I said to myself “My goodness, some day people like me will end up in jail.”

The good news is that he made this realization and that he was in a position to act on it and make Interface environmentally responsible. If you’re an employee of an evil workplace, your main option is probably to get out of Dodge and find another job you can be proud of.

3: The higher your investment in the company, the easier it is to blind yourself

And I’m not just talking stocks. You can invest money, but also time and identity in your work.The more you have invested already, the harder it will be for you to realize that things are just plain wrong. This specifically means that the longer you stay, the harder it gets to leave.

4: Being part of a bad system changes your perception

And more than anything, the system you exist in can shape your perception. If everyone around you acts like “hey, spending your day knee-deep in cow guts is perfectly normal” or “sure it’s OK to cheat about the company finances – everybody does it” then you’re more likely to think so too.The Milgram experiment may be the most chilling reminder of this effect. In it, subjects were lead to believe that they were part of a study in learning that required them to give another test subject electrical shocks. In reality the other person was an actor and no shocks were given.

The study showed that 65% of the subjects continued administering ever more powerful electrical shocks – even though the actor was screaming in pain and later on pretended to pass out. The subjects were never pressured – if they protested they were simply told in a calm voice that “The experiment requires that you continue” or “You have no other choice, you must go on.”

Here’s part of Milgram’s chilling conclusion:

Ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process. Moreover, even when the destructive effects of their work become patently clear, and they are asked to carry out actions incompatible with fundamental standards of morality, relatively few people have the resources needed to resist authority.

So when people in authority tell us to do something that we know is wrong, when the entire system just acts as if unethical, damaging behavior is just business as usual, many of us are powerless to resist. You may think that YOU are exempt from this, but in reality we’re all subject to this effect.

This is part of the reason that the Enron scandal could go on for as long as it did, even though many people inside the company ought to have known that something was rotten: everyone acted like everything was fine. As in “The company requires that you continue.”

Ultimately, it may even explain something like Abu Ghraib.

What’s your take?

Have you ever held a job in a horrible business? What did it do to you and your happiness at work?Related posts: